It's a chaotic world. We're just living in it (for now)

Headed into the apocalypse equipped with little more than some Minions memes and the urge to YOLO.

This issue I’m coming to you live from an existential prison of eco anxiety, driven by this cross-continental heat wave that’s dominated the news cycle the past couple of weeks. It’s all feeling especially spicy given that I’m currently in Seville, where it’s been 43°c (109°f) for the past three days. Far from leaving me feeling like an extra in a Britney Spears video from the ‘90s (I wish!!), I’m feeling gross, grumpy and deeply anxious about the state of the world.

In the context of melting runways, lakes literally becoming deserts and news segments with meteorologists that are more absurd than fiction, chaos is actually a pretty apt subject. This is an essay I adapted from a piece I wrote a month or two ago for the Creative Review, which was originally published here.

Scroll to the bottom for some quick links 🔗

“Complete disorder and confusion” is how chaos is defined in the dictionary. It’s a pretty apt description of what occurred in the Louvre earlier this year, when a ‘climate activist’ touting a wig and some potentially misguided ideas disguised himself as an old woman in a wheelchair, and tried to vandalise the Mona Lisa with a slice of cake.

After his bodged endeavour to smash the bulletproof glass that protects Da Vinci’s masterpiece failed, he settled for smearing said glass with cake, tossing a bunch of roses at its feet, and removing his disguise, Scooby Doo-style. As he was carted off by security, he turned back to a crowd alit with phone cameras. “Think about the Earth,” he declared in French, “there are people who are destroying the Earth, think about it!”

The stunt went viral. Google searches for ‘mona lisa cake’ and ‘mona lisa attack’ skyrocketed, while videos of the moment have blown up across platforms. The monolithic discussion around climate change, however, has rumbled on unchanged (heatwave notwithstanding), slowly creeping higher along with our collective anxieties. Does this mean that the attacker failed?

In terms of activism… probably. But we can still learn a lot from how the story unfolded online. While the attack may not be a case study in excellent activism, it’s an excellent manifestation of the ways we communicate in the current cultural climate.

Why does the internet love chaos?

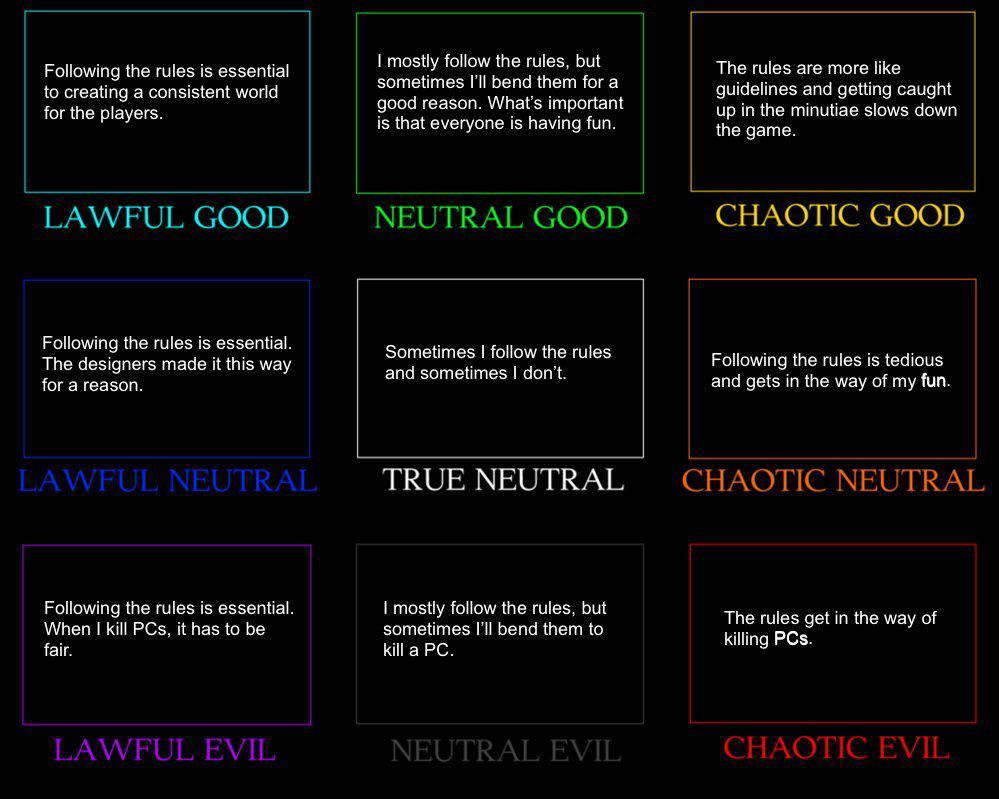

Recently, chaos – or more specifically, ‘chaotic energy’ – has become increasingly prominent in memes and media coverage alike. The origins of chaotic energy could potentially be tracked back to one of my own first run-ins with it: Character Alignment Charts. For the uninitiated, they look like this:

According to Know Your Meme, the two axis – ‘Lawful, Neutral, Chaotic’ vs. ‘Good, Neutral, Evil’ – originate from the 1977 release of Dungeons and Dragons. Sometime back in the late ‘00s, the internet got hold of it, and like so many artefacts of offline culture of yore, this chart was translated into a meme onto which cultural characters and references of any kind could be mapped. Nintendo characters. US Presidents. Quarantine hobbies. Etc.

The ‘Chaotic Good’ combo has always been especially appealing to me (lest anyone condemn me as True Neutral’). And it seems in some ways this joyful brand of chaos is more relevant today than ever:

1. Chaos is a manifestation of the new YOLO agenda

Young and extremely online audiences (read: Gen Z) are embracing a more chaotic existence. Having spent their young lives carefully pruning every inch of their lives into risk averse perfection, now, they’re reconsidering the benefits of a life perfectly projected online.

Apps like TikTok and the emergent BeReal (which has recently climbed to #1 among free apps in Apple’s US App Store) appeal to a mentality that asks why we should be maintaining a glossy public persona when there are so many more troublesome issues to worry about (student debt, climate change, mental health, etc.). Even the interfaces of these apps are chaotic, rejecting the familiar, streamlined swiping of the ‘complexion reduction’ signature to the social apps before them.

Recent data shows that the ‘most saving-savvy’ generation (yep, Gens Y and Z) are also moving into more ‘apocalyptic’ spending habits, splashing their hard-saved cash on holidays and hobbies instead of homes or the future. A full 45% of 18- to 35-year-olds “don't see a point in saving until things return to normal” – and so they’re spending now instead. Younger generations are YOLOing hard, leaning into widespread disorder, rather than trying to fight it.

2. Chaos is a source of escapism

This chaos is translating to the media we consume, too. Online, consider the ‘wrong answers only’ trend, and the widespread popularity of ‘Never Let Them Know Your Next Move’ TikToks, the latter of which have collectively drawn over 2.2 million views on the platform. Elon Musk’s recent saga with Twitter sometimes seems like he might be playing ‘Never Let Them Know Your Next Move’ with the internet as we know it.

The currently omnipresent ‘00s aesthetic is chaotic. The BTS boys share ‘the same chaotic energy’, apparently. Literally everything Kanye West does is chaotic. Speaking of – Julia Fox, with her DIY eyeshadow and intense supermarket looks, is a queen of chaos. The attack on the Mona Lisa? Pure chaos. And don’t even get me started on the fact that Minions: The Rise of Gru – darling of Gen Z’s chaotic internet humour and the latest addition to the Despicable Me universe – set box office records earlier this month, raking in more than $125 million.

The latter example in particular highlights how chaos can facilitate collective escapism. One of the biggest trends to ride Gru’s coattails in the past month has been #Gentleminions, which involves large groups of teenagers heading to the cinema in suits and formal dress to see the movie. Videos are overlaid with captions like ‘30 tickets to minions please’ and ‘felt despicable so i bought out the theatre’.

What’s interesting about this trend is that it’s an online movement designed to elicit offline chaos. Ryan Broderick of Garbage Day says it best: “Gentleminions is obviously both nostalgic and ironic, but it’s less focused on expressing irony than it is about using a piece of internet content to actively mobilise people. It’s about bringing a bunch of people together, doing something objectively weird, and then sharing videos and posts about it back on internet platforms with the expressed desire of inspiring others to do the same. It’s about testing the limits of what’s possible, not digitally, but physically and culturally.”

In other words, it’s about connecting people through a shared experience of chaos (whether you participated or just scrolled the hashtag), that’s not only fun, but has nothing to do with any of the realities of the world that get us down.

3. Chaos is a means of rebellion

Most importantly, chaos is often used as a means of pushing back. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, trust in global institutions has declined, economic volatility has heightened and populist politicians have seen rampant success. Chaos is the status quo in a volatile cultural climate.

As cultural commentator Max Read writes on his Substack of the years since 2016: “Facebook and Donald Trump are both creatures of speculation in an age of volatility, at once beneficiaries and producers of chaos and uncertainty. It's not (necessarily) that one emerges from the other, but that both are consequences of a particular, financialized approach to the world — one that seeks to profit from, rather than eliminate, chaos.”

Chaos can be used as a way to stick a middle finger up to the establishment, one-upping one brand of absurdity with another. It doesn’t have to be that deep – a cultural climate of nihilism means that we’re not necessarily out here to change things – but it does need to be fun. In this context, a lot of brands successfully harness chaos to such ends. Balenciaga revolted against the rules of high fashion when it conceived of the heeled Croc, and people loved it. When McDonald’s partnered with Saweetie to create a meal that dismantled everything we know about how you’re supposed to eat a burger, people ate it up. Never underestimate the attention-grabbing powers of chaos.

But the Mona Lisa attacker missed the mark when it came to harnessing chaos for rebellion.

To bring it back to this guy for a sec, when it comes to effective activism, the theatre in The Louvre fell down. The attacker may be rubbing shoulders with other forms of chaos, but instead of sticking it to an institution responsible for the slow demise of Mother Earth – fast fashion, big oil or big food, perhaps – it was directed at the less relevant institutions of art, history and France, ultimately reframing him in the public discourse as a virtue signaller and an attention seeker, rather than an activist.

This kind of misguided chaos is commonplace in ad land, too. Corporate beer brand BrewDog has built its story on guerilla marketing that ‘rebels’ against Big Beer, despite not only achieving Big levels of revenue of £286 million in 2021, but Big levels of toxicity in its work culture, too.

Pride month (when this piece was originally published) is a perfect time to spot brands in the wild making similar faux pas: putting out stands against homophobia in the form of free giveaways, rainbow-themed products and wildly misguided statements of allyship. Earlier this month, a Canadian oil company was forced to rescind its ad for ‘hot lesbian oil’. No, really:

Rebelling against an institution or norm without conviction or authentic action is a great way to let people know you’re doing it for the cash or the clout, but definitely not because you actually care. The attack on the Mona Lisa made for excellent content, and a great water cooler moment in a fragmented media landscape. But that wasn’t really supposed to be the point.

Other stuff from around the internet:

@CelebJets, Twitter

In keeping with the unintended theme of today’s newsletter, I’ve gotta highlight this Twitter user, who basically tracks celebrity jets and shames them accordingly (this Tweet about Kylie Jenner’s 17-minute flight across California went down particularly badly). There are many reasons this is interesting, but if I’m honest, I mostly love because it makes me feel a little better about my own carbon footprint.‘Good Minds’ (2022)

Good Minds is an NFT project and indie art project that's foregoing a Discord channel. While this project is pretty niche (I discovered it through universally beloved Substack, Dirt), the move to not launch a Discord channel is important, as it hints at one of the biggest issues with the current web3 promise from a user experience POV: major notification fatigue.‘Did people used to look older?’, Vsauce via YouTube (July 2022)

This is a fascinating exploration of a concept that lives rent free in my brain, and seems to surface more and more often the older I get. Veteran YouTuber Vsauce (who interestingly is yet another creator to have recently resurfaced after a months-long hiatus) explores the ways perspective, style and nostalgia impact the ways we understand both others’ ages and our own.'Google exec suggests Instagram and TikTok are eating into Google’s core products, Search and Maps', TechCrunch (July 2022)

The TL;DR is that Gen Z are switching out Google Search for searches on social platforms. Reddit recently came up in a load of press as an alternative to Search (or adding 'reddit' to the end of your Google search) as a means of finding more useful results, but it looks like it’s not the only one: according to this article, about 40% of young people are using Instagram and TikTok for search instead of Google, too.‘The End of the Millennial Lifestyle Subsidy’, The Atlantic (June 2022)

This is a great article on the unique ways inflation, rising fuel prices and a tanking post-pandemic economy will impact the small luxuries that many privileged Gen Yers (including myself!) have grown accustomed to: cheap Ubers, PostMates, DoorDash deliveries, etc. While this is, of course, far from the most pressing issue society faces, it could have some pretty interesting implications on the way Gen Y spends and budgets.‘How fans created the voice of the internet’, The New Yorker (June 2022)

The recent release of Kaitlyn Tiffany’s semi-autobiographical analysis of fandom – titled ‘Everything I Need I Get From You’ – has been pretty broadly covered in the watering holes of the internet where I spend my time. But this synopsis unearthed a particularly warming insight that I recognise from my own loose ties with fandom. Whether you’re watching an episode of Love Island to distract yourself from a painful revelation in your personal life, or listening to One Direction on your AirPods while you explore a new neighbourhood you just relocated to, Tiffany’s book evokes “how your chosen mania can become the lens through which you process the world.”